This week I came across a fantastic resource that I want to recommend to any and all who are serious about solutions to support aging adults. (Or healthcare, for that matter, since older adults are the power users of healthcare.)

It is the Fit for Frailty report, the second part of which was recently released by British Geriatrics Society.

Part 2, “Managing Frailty” is particularly important, as implementing good care is generally much harder than identifying those in need of better care. (Focus on the constraint, people. Implementation is almost always the constraint.)

For geriatricians, this is a nice resource summarizing the best of what we do. If you’re in geriatrics, read it and enjoy.

But I think this is especially valuable for the entrepreneurs, innovators, and health problem-solvers who are interested in aging.

Your job, as I see it, is to take the best of what we know and do in geriatrics, and make it more easily doable by everyone: older adults, families, communities, clinicians with no particular training in geriatrics, and even geriatricians. (I am eternally in need of tools that will make doing what I’m trying to do easier.)

Now here is a wonderful document that outlines how we go about modifying healthcare so that it’s a better fit for frail older adults.

Thinking you’re interested in older adults but not frail older adults? Think again.

Although frailty does have its own characteristics and isn’t the same as being old, or having multiple chronic conditions, products and services that meet the needs of the frail are the healthcare equivalent of universal design.

That is to say, the approaches we’ve developed for frail older adults — like carefully weighing the benefits and burdens of medications, and tending to the needs of the family — are generally good for all patients.

Plus, frailty is strongly correlated with healthcare utilization, so if you develop tools to better help frail older people, someone might be willing to pay for them.

Must-reads from the Fit for Frailty report

- “What is frailty?” This is a good review of what is frailty, and how it can be distinct from multimorbidity. See also “Causes and Prevention of Frailty.“

- “Managing frailty” This page summarizes the core components involved in optimizing the health of a frail older person. I actually think most of these are good for all patients. Shouldn’t we “ensure that reversible medical conditions are considered and addressed” for everyone? Same goes for establishing systems to share health information. Of course, great comprehensive healthcare is expensive and studies usually find it’s not economically worth it unless you target “high-risk” patients. But some of these strategies are things that “low-risk” people could do for themselves, or perhaps use health savings account funds for.

- Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment: This page details what’s involved in a geriatric assessment. Again, much of it sounds like things that are sensible to consider for all patients. The domains to check include:

- Physical symptoms

- Mental health (which includes cognitive function)

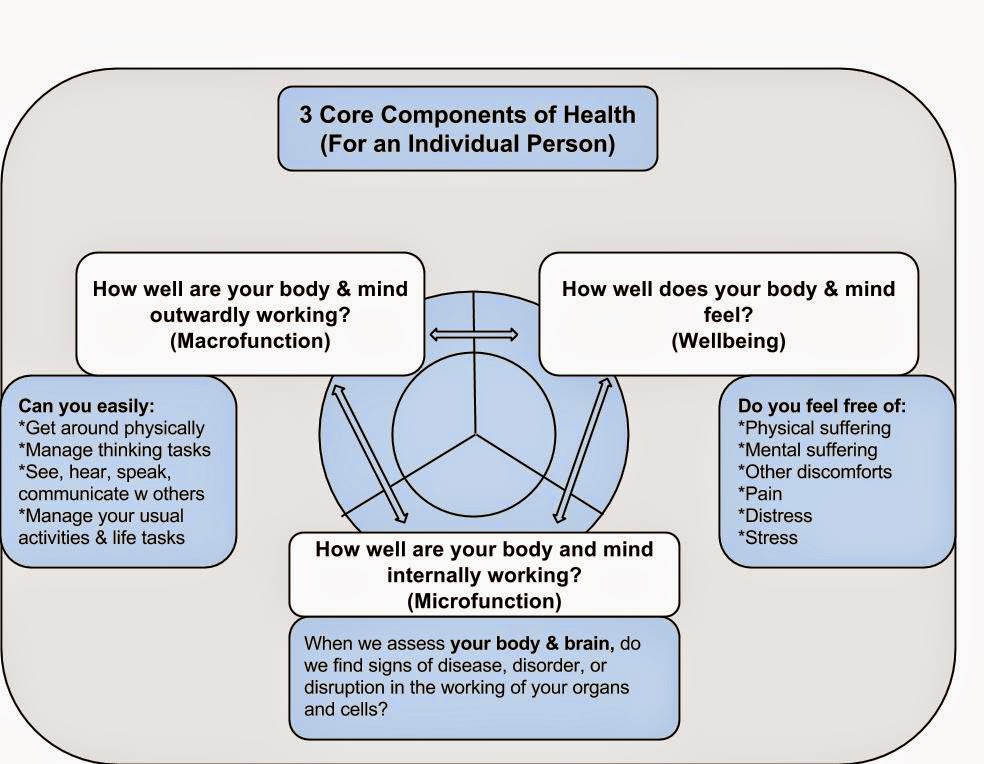

- Level of function in daily activities (oh wait, that sounds like the macrofunction in my recent “What is health” model).

- Social support networks currently available, both “informal” (family & friends) and “formal” (social services). This report doesn’t include online patient communities but that’s becoming an increasingly more common form of social support, although your online peers generally won’t check your symptoms or pick up your medications for you.

- Living environment, which includes mention of “ability and tendency to use technology.” (yeah!)

- Level of participation and individual concerns. “i.e. degree to which the person has active roles and things they have determined are of significance to them (possessions, people, activities, functions, memories). Will also include particular anxieties, for example fear of ‘cancer’ or ‘dementia’. Knowledge of these will help frame the developing care and support plan.” In other words, understanding what’s important to a person!

- Compensatory mechanisms and resources that the person uses to respond to having frailty. For non-frail adults, it is generally relevant to figure out how they are compensating for whatever health problems they have, although we routinely neglect to ask about this in a rushed primary care environment.

- Holistic Medical Review: This is basically a comprehensive review of one’s health problems, and the current management plan. This means a careful check on the chronic medical problems, and thoughtful assessment to identify new health problems. This also includes a medication review. In other words, this is basically what one’s annual physical exam should involve, but often doesn’t.

- Individualized Care & Support Plans: This page describes the key characteristics of a good care and support plan (CSP). I love love love that it’s described in part as an “optimisation and/or maintenance plan,” because that is exactly what is involved when it comes to older adults: optimizing rather than curing. Particular highlights include:

- Determining what the person’s goals are

- What actions are going to be taken

- Who is responsible for doing what

- The timescale and plan for follow-up and review

- An escalation plan which describes what patient and caregivers need to look out for, and what to do.

Help and Innovations Needed

Needless to say, it’s currently hard to do the things above consistently. Even geriatricians struggle, because it’s there’s a lot to cover and keep track of. (I’ve often thought that what we need is to build on project management software for care and support plans.)

Understandably, it’s hard to come up with tools that are a good fit for the complexity at hand, esp since healthcare as usual is already spectacularly ill-suited to properly managing complexity and allowing patients to participate.

But at least we now have a good resource to summarize what we can work towards. Fit for Frailty offers a blueprint for the kind of comprehensive person-centered care that everyone can benefit from.

Is your work fit for frailty? Shouldn’t it be?